HeRSToRy 004 Michelle Crone

Date: August 24/25, 2006

Location: Provincetown, MA

Present: Estelle Crone, hershe Michele Kramer

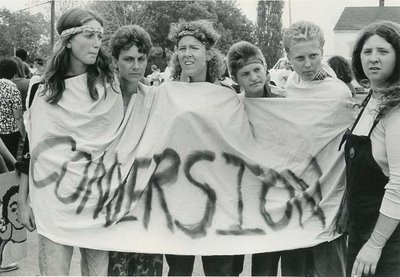

“Michelle Krone [sic] stands at entrance to camp near Army depot in upstate New York.” Boston Globe, July 1983

“Michelle Krone [sic] stands at entrance to camp near Army depot in upstate New York.” Boston Globe, July 1983Michelle Crone was one of the early organizers of the Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice. She lived in Albany, NY at the time and was a trained facilitator with several years experience in organizing women’s music festivals. She was hired on in a paid position at the encampment in the spring of 1983 and remained involved, often as a meeting facilitator, through 1985.

*Conversation transcribed verbatim (minus “um, like, I mean and you know”) by hershe Michele.

AUGUST 24, 2006

H: Michelle Crone. It’s August 24th, 2006. We’re in Province…Providence…

E: Provincetown.

H: Provincetown.

M: Big dif.

H: Sorry [all laughter]. This is a west coast person. Cool, so why don’t we start where you were telling us that your understanding of consensus process and all of that that was so huge at the camp was something that you brought with you when you got involved.

M: I did.

H: Can you talk about it?

M: Actually I think I have to start when I started going to women’s music festivals in I think, ‘79 or ‘80. What was it ‘79 or ‘80? There was a whole group of us living in the Caribbean trying to create an alternative culture. Three Mile Island (1) happened so we came back. We got back in the states and we immediately heard about the Black Hills Women Survival Gathering the Lakota Nation had called it and the women were calling for a gathering before the larger Lakota gathering. So we went to that. It was Punk Mary, Kendra, myself, Ruthie. We got blown away as to what was happening [hershe laughter] with the Three Mile Island reality and the uranium mining and the Lakota prophecy starting to come true when the white man takes the black stone from the mountains and the water becomes polluted and that’s the beginning of the end for people, for the people going from the earth upward into the sky. We were all totally, totally, totally blown away and I had been an organizer before that – I did welfare rights organizing in the Appalachians in the 60s and I was, I started a halfway house for women coming out of the psychiatric ward in the Caribbean, I started a 24-hour crisis intervention service, I was an old-time organizer even at that point. And what everything that we heard just blew me away so much that I had heard about this place called ‘Michigan’ (2) and we’re back on the road and I say to, I think it was Mary Gemini, I said “Let’s go to that place and get women energy.” [hershe laughter] And she says, “Well, where is it?” and I say, “It’s in Michigan somewhere [hershe laughter] – why don’t we just call and see if we can go there?” And so we stopped at truck stop, we made a call, she came back to the table and said, “Oh, they said ‘no.’” And I said, “Oh no, no, no, they don’t realize, it’s not a matter of yes or no, we have to go, we will go, we need to have that kind of healing energy.” So I called and I said, “We have to go, we are coming and that’s it.” So we arrived on the land, there were only 8 other women on the land, this is the old land, and that was the beginning of my involvement and the other women’s involvement in music festivals. And so that’s way too many stories and way too long a time but through the women’s music festivals we created amazing circles. And Michigan at that time was truly a revolutionary movement and it was all about community, it was all about sisterhood, it was all about listening to who we were, challenging our fears, not abiding by what we’d been told could or could not happen as women, etc. etc. And in 1982 when a group of women from the War Resisters League (3) and the Friends…Friends…is it the Friends Society (4), the Quaker groups out of Philadelphia?

H: Mm-huh.

M: People were starting to call for a show of solidarity to, for, with the women of Greenham Common (5) in England. And how that had started out in England was there’s patches of land that’s commonly owned by all the people of the country and there had been men and women who took over a patch of land outside of one of the bases where the Cruise (6) and Pershing (7) missiles were sent to from the United States and they had a really hard time in terms of gender clashing, etc. and then the women…how we were told, the women kicked the men out and later on down the road the women also established another encampment next to the gates, there were certain gates around Greenham [inaudible] and some Greenham women had come over to the States to try to do some fundraising and the peace organizations decided that we needed to do something in solidarity to help them out but we didn’t want to do a one-day action.

”An estimated 4,000 women turn up [at Greenham Common] to blockade the base. Some manage to enter and plant snowdrops.” Guardian, December 13, 1982

”An estimated 4,000 women turn up [at Greenham Common] to blockade the base. Some manage to enter and plant snowdrops.” Guardian, December 13, 1982We had done the Wall Street stuff and a lot of other kinds of civil disobedience and things. We didn’t want to do that, we wanted to do something that was more lasting and we wanted to do something that didn’t necessarily evaporate after a one-shot deal in an urban setting. And so what we figured we should do is to look around and see where these Pershing and Cruise missiles actually originated from and of course it’s in rural parts of the country. It’s always in rural parts of the country and it’s always…well, not always, but almost often on native sacred lands that the military had gone ahead and gotten their military bases on which we don’t think was any real coincidence [hershe laughter]. And so we used to have meetings in Albany and in New York and in Philadelphia, etc. and we always operated through consensus and I believe that the Quakers, the Quaker groups brought the consensus into that whole process. We had always used consensus at the music festivals so we kind of combined the traditional Quaker sense of consensus along with our lesbian, radical, often times separatist sense of consensus. And so.

H: Can I ask a question?

M: Yeah.

H: So were those mixed groups or were those women groups?

M: Women groups.

H: And was there a name? Did you guys create an organization to do …think about a peace camp?

M: No we didn’t, it was a collaboration.

H: OK, so it was just what happened.

M: Yeah, it was a collaboration. So everybody was looking, they looked at, I think it’s Griffen…?

H: Griffiss.

M: Griffiss? The Air Force base in upstate (8)?

H: Um-huh.

M: And they looked all around that area as to what was being done where – the Seneca Army Depot (9), the Air Force base, the naval thing up there in Lake Geneva. It was just ripe for exposing how much the military had actually taken and employed enough of the local people to pretty much run the place. Nobody questioned, nobody ever had any kind of protest ever.

”Roadside view of property that extends back to Seneca Army Depot.” Nuclear Times, May 1983

”Roadside view of property that extends back to Seneca Army Depot.” Nuclear Times, May 1983And so it was myself, a woman from Nuclear Times - the magazine- and I want to say it was possibly Karen Beetle [see PeHP Herstory 003] who was the third party. You spoke to her, did she mention finding the land?

H: She didn’t…not that I recall.

M: There was a third woman and I can’t remember who it was.

E: Nuclear Times was that out of Rochester?

M: I don’t honestly remember, I don’t recall.

E: The picture on the postcard was that from Nuclear Times?

H: I don’t know.

E: Okay.

M: I know somewhere there’s floating an article from that magazine of the three of us.

H: Uh-huh. We have that.

M: I have, I remember having a gray hat tilted to the side and I had really long hair at the time. I remember that was a part of, that was in the article and if you do have that that’s great because then you have the times and the dates and who those people were. So we were out driving around dah, dah, dah. And there was a piece of land in…near Romulus and Varick that had been abandoned, well, not abandoned but it had, it was, there was no one living there when we saw it. A older woman, I think, lived well into her 90s – it was her place and when she died she left it to her grand niece…

M: Her niece.

M: So the three of us just ran over there and it was a Sunday and it was muddy. I think it was in March. It was really, really muddy [hershe laughter] and we were in the car, “Well, what are we going to say? Who are we going to tell? We don’t want to exactly say that we’re going up against the military establishment [hershe laughter] and we want your land because it butts up against the base. But then we don’t want to lie.” So we went in and I remember being very concerned, she had a very beautiful house. I was really concerned about the mud being on her carpet and it was a Sunday and somebody had given me the name of a pastor in the church that she attended and that was our entre into her house. I had mentioned his name and that we wanted to do, I don’t think I called it ‘social change.’ I think I called it ‘educational work for peace.’ And so she invited us in and she gave us tea and cookies and, “What kind of peace do you want?”

“Well, world peace and we don’t want wars and we want to educate people as to how wars are perpetuated and how we have to live through the spirit.” We really stretched it kind of stuff, but everything actually, it was all true. It was all elements of truth. So, lo and behold, “We’d like to buy this land from you and how much does it cost?” And I believe, I believe that the price of the land was 56 thousand dollars. Either 36 or 56.

E: 36, I think.

M: It was 36?

E: Yeah.

M: Okay, 36 thousand dollars. We had between us maybe $20 [hershe laughter], right? And it was like, “Oh, 36? That is no problem, how much do you need for a down payment.” And we figured out that it was going to be three thousand dollars, I think, for the down payment, 10%, right? Three thousand six hundred.

”Organizers Eberlein, Cooper and Crone in front of house on prospective campsite.” Nuclear Times, May 1983

”Organizers Eberlein, Cooper and Crone in front of house on prospective campsite.” Nuclear Times, May 1983And we went back and started doing the networking with all the collaborative groups. We came up with the down payment. We didn’t know how we were actually going to meet the mortgage payments. All these people, well, here are the lawyers out of Boston, they’re going to work up how to do a corporation so that no individual is going to be held responsible, and yes, here’s the War Resisters League and there also a group in Syracuse that did the calendars.

H: The Syracuse Peace Council (10).

M: The Syracuse Peace Council.

H: And Women’s International League…

E: Yeah, when did WILPF come into it?

M: The War Resisters League?

E: No, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (11).

M: They were there from the beginning.

E: From the beginning.

M: Yep, they were. Mandy Carter was connected up.

E: Mandy, okay. I just saw Mandy on TV recently.

M: You did?

E: Yeah, anyhow.

M: So everybody, all these corporations kept throwing their resources and their skills as far as fundraising in and their, email didn’t exist, but their mailing lists and all that kind of stuff and everything we needed we got and along the way we paralleled with our process, creating our process. Consensus, male children, male involvement, etc. etc. So we were doing a parallel of logistics and a parallel of philosophy and policy kind of stuff. And we got the land which was really impressive because, [laughter] because we had no money, it was very magical, but that area of the country had been settled a lot by the Amish (12) families and it was 56 acres, right? 56 acres?

E: 53.2 or something.

M: 54? 56? 50 something.

E: 53.2 I think.

M: And they…

E: 52.3

M: …that’s exactly the size that a son would get from a family if he was 2nd or 3rd and 4th in line because the eldest would inherit the father’s. The eldest would take care of the mother and the father. But the 2nd, 3rd, 4th would have to get their own so that was the exact amount. Because we had an Amish family next to us and then on the other side we had the trailer park. And so we were very lucky to get that because later on we were, we had met a lot of farmers who were trying to get that, who were not Amish as well. So could you check the time for me, hershe?

H: Yeah.

E: Michelle, so, did you already have a connection with Shad and Jody?

H: 9:23.

M: What is it?

H: 9:23.

M: 9:23. Yeah, we did, we did Michigan.

E: Through the music festival.

M: Yep. Yep.

Woman playing the guitar behind the farmhouse. Nancy Clover, Labor Day, 1983

Woman playing the guitar behind the farmhouse. Nancy Clover, Labor Day, 1983E: Michelle, for some reason I thought you had been in on Michigan since, almost since its inception.

M: No. I lived in the West Indies for 11 years from 1969. I’d been out of the country. I came back into the country when I thought it was okay for me to come back into the country [laughter]. And I went up into the mountains of New York and there was a thing there called the Woman’s Place and it was a lesbian separatist land group and that was all networked around New York City and Boston and so I had a cabin near there and so that’s how I got connected up with a lot of the people – I think Shad was also a part of that and a lot of the women who we then tapped for Seneca came out of a Woman’s Place as well.

E: Oh, okay.

M: So it was really like that area and the music festivals and it was just all these great grassroots networks and we had a lot of skills. I basically got trained by the government how to organize in the 60s before they realized that who they were training, not just me, but who they were training, they were taking those skills and organizing against the government [shared laughter] for social change [shared laughter]. So.

H: So should we stop? You gotta get going.

M: Yeah, I gotta go down. Is this the kind of stuff you want?

H: Exactly.

AUGUST 25, 2006

H: So you kind of wrapped up the how you got there and what the influences were but, maybe…

M: Oh, all the collaborative stuff that was going on and we got the land. And then people wanted me to apply for the one and only funded position.

H: Okay.

M: And it was like, oh, do I really want to do that? Well, I did it. I was interviewed after a meeting in Albany – Jody went for the job, I got the job.

H: Which was?

M: The only job there was [laughter] … the job, the staff job, the one staff person. So I packed up my things, drove out to the house and lo and behold I get there and there’s Jody! [aughter]. I said, Jody, I thought I got the job? [shared laughter]. So I said “I guess we’re going to split the job – we’ll co-job it.” So that’s how Jody and I became the first and only staff people. And then it was, the house was completely empty but it was May, I remember, and the college students were leaving Genesee and we had a call from a woman, I can’t remember her first name now, but later is was Samoa.

H: Kim.

E: Kim Blacklock.

M: Okay. We got a call from Kim who was running some center connected up to the college or university and so Jody and I rode over there and she said, yeah, we have furniture so we loaded up this stuff – it was a couch with three legs [shared laughter]. We furnished the house with pretty funky stuff, right, and I remember seeing Kim, she was huge! She must have been like 6’ something and she was really big and she had a ponytail pulled back and one of those football jerseys [hershe laughter] and a skirt, she had a skirt on! She didn’t know what Jody and I were all about and we didn’t really care too much what she was about, we just needed furniture – we had nothing. But it was really interesting, you were talking earlier Estelle about how the Encampment touched lives, changed lives – to track this woman’s life would be a radically visual journey because the last time I remember Kim, Samoa she was…

E: She’s back to Kim.

M: Is she back to Kim?

E: I haven’t seen her in, talked to her 10-15 years but she had gone back to Kim.

H: There you go.

E: But she had been to Samoa and met her people and was much stronger about her connections…

M: Cool.

E: …she was a minister’s daughter.

M: Was she?

E: Yeah, yeah.

M: Well, so from the image of her in a skirt and jersey to …

E: I still see her in boots and a skirt, yeah.

M: Yeah, to see her, I think she was either eating fire or walking on glass [shared laughter] in the back, it was quite a leap. But then we started doing everything you needed to do to get ready to be an encampment without letting anyone know that we were going be an encampment. So we were actually starting to implement the logistical part of it while the philosophical policy parts of it were still being crafted. We were a part of that as well, in terms of the meetings, once we had the land the meetings started to happen on the land and we had to decide how far back men would be able to go and all of the things in terms of access and how old is too old for male babies? I remember that meeting, that actually took place in Albany and there was Kate Donnelly, I think it was Kate Donnelly who made the buttons and she had a little baby boy and there was a woman there, I forgot who it was, who had a little baby girl, I mean babies, toddlers, and we’re having this big debate, “No, it’s not inherent within the male gender to be violent.”

“No, it’s environment.”

“No, if you’re raised by loving people.” And I’m looking at the two babies and this little baby boy picks up this thing and hits the little baby girl on the head [laughter] and it’s like, well, all right, so…[laughter]. But those meetings went on forever!

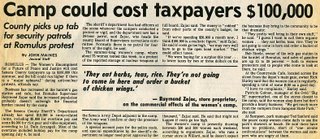

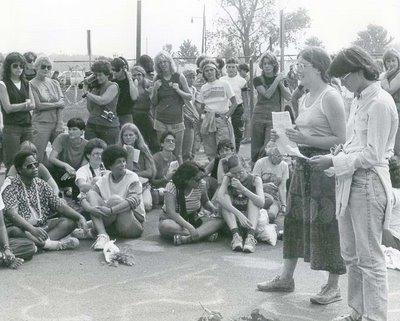

Nonviolent civil disobedience training. Nancy Clover, August 1, 1983

Nonviolent civil disobedience training. Nancy Clover, August 1, 1983 All right so back to the house - we’re learning a little bit more about the older woman who lived there, like, she lived there alone and she seemed to be an amazing person I wish that I had known her. We found this little dug-out area it wasn’t the root cellar, it was under the living room and we were wondering if that house hadn’t been a part of the underground railroad and that was the hiding place – somehow, I feel like that truly was. We started getting all the data in from the people doing the research in terms of the military presence and what that meant within the area - that that county had the highest rate of cancer and that the Manhattan Project (13) tailings had been dumped in the Seneca Army Depot and that sightings of white everything in there was pretty common - white deer, white fox, white skunk, white everything and so we started to trying to figure out how to put all that together to do outreach educational things because it wasn’t just the presence of us as anti-deployment to the base it was also educational stuff to the community and how we could talk about conversion of that area into a place that was much more of a healthy lifestyle for the local people and not to be so dependent on the government. We had to go through many, many steps in terms of getting permits to have people there. We were going out to meetings with county and meetings with all kinds of officials. I remember we had to set up a huge town meeting that was held at the fire station because people were wondering, “Who are those strange women at so-and-so’s house and what are they doing? Some kind of what? Some kind of hippy peace thing, what?” [hershe laughter] And we would get a farmer coming by saying, “Look, I got 40 bales of hay and you girls are going need to put the hay in the back there because that grange thing…”

We’re, “Oh, okay!” And we were trying to draw up plans. I remember creating an office in the house with no furniture so we went to the barn and we found where the chickens used to be and underneath there was this really long plank so we took that out and scraped the chicken shit off as best we could [hershe laughter] and we put that, that became our desk in the office. But we never really got all the chicken crap off of that – it was an ongoing joke between Jody and I. And Jody was a great logistical person - you could say, “Jody we need this built” and she would have three pieces of material and sooner or later you’d have that. But in terms of her social skills at that time… [hershe laughter] it left a bit to be desired. When we would go into meetings, I pretty much became the mouth [laughter]. I used to do a lot of stand-up comedy kinds of stuff so I have always used comedy for a tension relaxer or just an outright break-the-hostility thing.

H: Whatever the case may be.

M: So we would go into these meetings at Varick and the little town meetings in Romulus and more times than not we were doing pretty okay and they were laughing and as soon as people laugh the threat is diminished so we were doing pretty okay in terms of getting our permits and getting acceptance and stuff and more people were coming around from the community and two women came over and said, “We have a tractor we can bring over.” And that kind of thing and the town hall meeting was coming up.

H: So before you tell us about the town, how many women would you say at this point were a part of these meetings and core organizing and making these decisions about logistics and blah, blah?

M: Well, it depended on where, if the meetings were being held in Albany or New York or Philly – it was much more. If they were being held at the Encampment, maybe 15, 12 or 15.

H: OK

M: Because it was far, as you know, it’s a bit out there and that’s what the military likes and that’s what we were searching for. And we didn’t have much water stuff going on and the rats there were pretty bad. On one of our trips Jody had, I think it was coming back from Michigan, we had stopped in Pennsylvania and they had these rest stops that were environmentally friendly so Jody thought we should try to go and build those so she was working on that design [hershe laughter], how to build those. We were going to use the methane gas for power – we were coming up with everything. We were going to plant red clover and harvest that it was going to be organic and it was going to go to all the coops and that was how we were going to pay the taxes, etc. [hershe laughter]. So there we are at the town hall meeting and it was packed – there must have been two, three hundred people there - for that area that meant every household came. They wanted to know who we were and how come it was just going to be women. And we were talking about, “Well, as women we have traditionally been put in roles where we were made to feel as though we couldn’t do things on our own so this is, a, was and, a chance for us to prove that we can.”

Women building the boardwalk to make the encampment accessible to all. Nancy Clover, August 1, 1983

Women building the boardwalk to make the encampment accessible to all. Nancy Clover, August 1, 1983We were really like, oh god, I felt like I should have white lace dress on with big hair [shared laughter]. There was this one guy – he was just adamant about, [in a deep, slow voice] “Women can’t do it, just can’t do it! What if something happens and there’s no man there to protect you? What are you gonna do?” I wish I had a camera on this because Samoa [shared laughter] slowly rises up from her chair – slowly and she just kept going and you could see everybody in the room just going…[miming watching someone growing tall] and just kept going [hershe laughter] and by the time she was up, and I’m sure she stood on her tippy-toes because she was even a little taller than she really, truly was, she just said, “I don’t think it’s going to be a problem.” [shared laughter]. And everybody just burst out laughing, man, and that was it for ‘what are you going to do if a guy comes on.’ So, and we were, that was a success. We did a bunch of those things. We went to July 4th stuff, we ate chicken. Jody and I would always joke about having to eat so much dead bird. Things were going along really okay, fine…

H: [camera slips, righting camera] Okay, go ahead.

M: We were, we were, were gaining a lot of momentum. It was gaining a lot, a lot of momentum out … I don’t know if it was all of the work the different organizations were doing in their communities combined with the fact that we were in solidarity in support of Greenham and they were getting quite a bit of press because of the Cruise missiles that were being documented, but we started getting media calls from not only the less-mainstream media but also the international press.

“The Greenham Common protests were to gain a more significant profile in the US in November 1983 when federal court action was taken by some of the women against President Reagan in an attempt to ban him from locating cruise missiles in the UK.” Guardian, July 4, 1983

“The Greenham Common protests were to gain a more significant profile in the US in November 1983 when federal court action was taken by some of the women against President Reagan in an attempt to ban him from locating cruise missiles in the UK.” Guardian, July 4, 1983So this of course was the time where we had no leadership – we will have no leadership, there will be no leaders, everybody must take a part of the responsibility for everything [laughter]. We will have no spokesperson for the media. Everybody’s a spokesperson. So we did some really quick bullet points as if you speak to the press, this is what you say in terms of what we want to get over. You can express your opinion about anything but what we want to get over are these bullet points in terms of the money and the perpetuation of the war, criminal sensitivity of the military and all of that kind of stuff, so…

H: Let me interrupt for just a second, so that idea of no leader…

M: Mm-huh.

H: …that was a philosophy that you all had already discussed? Was it pretty across the board folks felt like that, there was not a lot of…?

M: Yep.

H: …that was just the way it was going to happen and everybody was on board with that.

M: That was it. And we talked a lot about lesbian visibility because traditionally if you were to look…[audio tape stops]

H: [changing audio tape] If you were to look…

M: If you were to look at your social change movements and you were to look at the core of the workers more often than not a large proportion would be lesbian powered. And yet as you would come from the organizing circles out to the mainstream to create that social change, lesbian visibility became almost nothing. So we were going to not allow that to happen so we talked a long time and came up with, of course we couldn’t call it a rule because we would have no rules, we could, I think we came up with ‘suggested…policies.’

H: Policies.

M: Or suggested, yes … the word ‘suggested’ was in there I remember, or guidelines … ‘suggested guidelines’ or something. We wanted to make sure everybody knew that you could be a spokesperson, and we rotated spokespeople by the day, but you could not say anything about lesbians. You couldn’t say, “I’m a lesbian,” or “I’m not a lesbian.” If somebody asked you directly about involvement, be honest, but there was no invisibility here and what we wanted to create was all people would be seen on the same level. We were trying to take away that copout of “I’m not a lesbian”…

H: Right, right.

M: …kind of a thing. That was a policy. It took a long time, a lot of discussion and we were getting closer and closer to the opening date and more and more people were coming. It wasn’t just Jody and I. In fact for a long time Jody and I had the luxury of having that whole house to ourselves. And then people were coming and taking places to sleep so we had to do policies about where you could sleep and what’s the common room and then of course if women are living together signage has to start going up about [hershe laughter] cleanliness – ‘Your mom doesn’t live here.’ Who’s doing the kitchen and what foods can come in and what can’t. Jody said, “I’m going to go get a bus.”

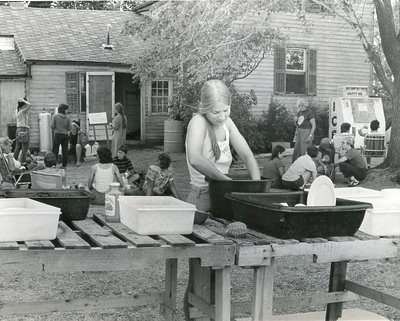

Woman washing dishes. Nancy Clover, August 1, 1983

Woman washing dishes. Nancy Clover, August 1, 1983It was just all this stuff and everything had to be meeting-ed about. Nobody could make a decision [hershe laughter]. Later on I remember, and I tell this often times when I’m organizing or if I’m speaking some place, I’ll tell about the decision about the rats. I hate rats, they are the only thing in my life that I’m deathly afraid of and they were getting really big and the whole thing, the whole group of women who didn’t want to poison rats went off to shower at the state park there and those of us who just wanted to get rid of the rats quickly held a meeting and reached consensus to poison the rats [laughter]. So there were certain ways you could get around it.

H: I think the Bush administration has made a few judge appointees that way.

M: Yeah right. Right. And we were playing around, “Well, we can’t let some women who’s really not all that balanced be holding our process up here.” So then we started consensus-minus-one, consensus-minus-two [shared laughter], which came in really handy when we started organizing the marches on Washington. I said, “Here’s a process we used at the Encampment, it worked pretty well.”

H: Had you guys done that consensus-minus-one at Michigan?

M: I think we invented that at the Camp.

H: Okay.

M: And it took us a long time to even broach that. At Michigan we tried to operate with consensus whenever we could however because there was a large amount of money what we managed to do was to separate – “Okay, your names are on the papers so you’re the bottom line when it comes to business, but we are the bottom line when it comes to policy.” So we would, we created the LUNTs - Land Union Negotiating Team and the CUNTs – the Coordinating Union Negotiating Team. So yeah.

H: I didn’t remember that.

M: Yeah, it was a very exciting time to create different ways of solving things that incorporated everybody’s input was really very radical. So anyway. We’re getting back, we’re doing pretty okay with the community and nothing had come out about being a bunch of radical lesbians… at the most it had been ‘Hippies, Peace Hippies’ and ‘The Girls,’ the ‘Peace Hippy Girls.’ a) “They’re not really that dangerous let’s drop them some food and give them some hay,” and like that but, then this guy, oh what is his name? Sometimes I remember his name and sometimes I don’t.

H: The flag guy?

M: Yeah, what was his name?

H: Emmett or something? Everett?

M: Everett? Something like that so he comes up and says, “Michelle, I want to give you guys some flags, some American flags for the Fourth of July.”

And I was, “Well, Everett, - I knew his name at that time, but I’ll call him Everett - I really want to thank you for that offer and I would gladly take that flag but we operated through consensus here and we have about 200 women on the land so it would take us some time to get back to you about a decision.” And this decision-making thing went on about the flag. It would go into, we would, it would go into 1:00, 2:00, 3:00 in the morning. We made sure that, oh, about the suggested policy or suggested guidelines, you could not make that with just one meeting – there had to be a whole series, three times you had to have meetings and it had to be, go out to other women who were not on the land because we were constantly trying to maintain the connection and the network even though people’s presence weren’t there it was really important for people to have a voice and a channel not only for the financial support but also for what [inaudible] were. So whatever we were doing around that suggested stuff would have to go out and this thing about the flag was so important that we had to go out. We were getting all kinds of input in so it was very challenging in terms of how do you make a decision even when people aren’t there? And so, myself and some other women we were very much advocating for the American flag to be accepted because I truly believed and I’m a historian, film history and also I just love history. Historically-speaking the flag is a sign of revolution in this country and so I was advocating for that and it wasn’t flying [hershe laughter] because more people were associating the American flag with at that time, Central America, and under the flag of oppression and all of that so it was constantly going in the direction of, “No way are we going to make the American flag accepted. We’re going to make our own flags on pillowcases! [hershe laughter] Yeah!” And then if you wanted an American flag you can put the American flag on the pillowcase [hershe laughter] and you can put that on the front lawn [laughter]. So it was a creative way, compromise, but I had to go back to this guy and say, “Even though I really…hmm, hah…collectively we can’t take your flag.” So what he does, he goes out and thousands of these little flags were everywhere. He gives a flag to everyone in the surrounding three counties and he starts to put it out to the media and to the officials, “These women must be communists, because they won’t take the American flag, dah, dah, dee, dah, dee, dah.” Penny Saver, a little, shows up – ‘These women aren’t only communists, they’re lesbians!’

“Oh, lesbian communists are out there!” And the mood starts to change [shared laughter]. People aren’t talking to us anymore in town, not so friendly when we have to get little permits. People are sneaking out from the base cutting the water line just the day before we’re getting inspected for our camp permit. When did we open?

”Being careful not to cross the line designating Seneca Army Depot property, the first of the counter-protestors wave American flags during pre-dawn moments of Monday morning’s protest at the depot. From left, Brian Compton, Waterloo; John Wood, Waterloo; Bob Appell, Seneca Falls, and Steve Lichak, Ovid.” Ithaca Journal, October 25, 1983

”Being careful not to cross the line designating Seneca Army Depot property, the first of the counter-protestors wave American flags during pre-dawn moments of Monday morning’s protest at the depot. From left, Brian Compton, Waterloo; John Wood, Waterloo; Bob Appell, Seneca Falls, and Steve Lichak, Ovid.” Ithaca Journal, October 25, 1983H: July 4th.

M: No, we didn’t do the fourth, we purposefully didn’t do the fourth. We didn’t want to…

E: July 5th, I think.

M: July 5th. But we got our lines cut either the 2nd or the 3rd [inaudible] final inspection in order to become, now we’re a campground because…

E: Michelle, can we go back up, because the flag thing happened, but before that, there was no way of knowing how many women were going to show up.

M: We had no way of knowing. We had no way of knowing.

E: And do you remember anything about WILPF’s involvement because I think that they were out there organizing on a national level and getting the money for the house and stuff.

M: They were, War Resisters League was, there were a lot of groups who were doing that.

E: Well, Shad especially mentioned WILPF on a, and thought that we needed a lot of information on what they did on a national level.

M: Well, I think Shad’s connection to WILPF was important in that, if my memory serves me correctly, WILPF carried a lot of the paper administrative stuff in their offices because we weren’t equipped to do that and that was kind of parceled out. So different people were doing different things, like different communities were putting the encampment booklet together and then different areas would do research on, like the Native policies that existed at that time, the tribes and how they operated in terms of decision-making and then other communities, I think it may have been Rochester/Syracuse were collaborating on civil disobedience and writing a history of that and then the lawyers were coming together because we knew that we were going to do an amazing amount of civil disobedience and we were going to have to have all of the support systems in place with the lawyers and the bonds and all that if people chose to do that. So that was all operating. Meanwhile back at the farm, me and, we’re, “What do you mean we have no water, the (inaudible) cut…?!?” Because they were sending people from the military base over at night and messing with our systems and things. In fact one time, this was before, this must have been in May, we went to a meeting and we came back and there were these guys leaving our driveway wearing hardhats and lots of wires and they wouldn’t stop, we tried to stop them to ask what they had been doing and so at that point we were pretty sure that that’s when we got totally bugged.

H: And that was when, do you have any idea? Or was it prior to the opening?

M: Oh yeah, that was in May. Later on when we had been there a while and people were coming forth and telling us that they had information for us we could never be sure what was being fed to us to mess with us or were people really having conscience-ness speak to them to let us know things. But there was this one person, and Shad can talk to you about this one person because she met with him later on, not that long ago and he revealed to her how high-ranking he was in the military in terms of the intelligence. But we were told, “Come take a walk with me,” and we had to turn on radios and he told us, “Yeah you’ve been, since the beginning, you’ve been monitored.” And told us even over in the trailer park they had some people in the trailer park monitoring us.

E: Oh yeah.

M: And to us it was kind of like a joke. We tried to keep minutes in the meetings and we’d often times say, “Let’s get the government to give us a tape so we’ll know exactly who said what when.” [shared laughter].

E: Right, right.

M: OK, so we’re getting up there now, it’s getting, it’s getting real close to the opening and the phone’s ringing off the hook, ringing off the hook. This is when we got a sense that, hey, this is going to be huge and we started hearing about the walks that were coming in that the Buddhist (14) monks and nuns and stuff were making.

Nancy Clover, 1983

Nancy Clover, 1983We had our policy in place - men could only go into the living area where our educational brochures were, they could be on the front lawn but they couldn’t pass the back. One of the things I’m most proud of is, we would get literally tons of phone calls from CBS, ABC, NBC, BBC – every magazine - Newsweek, Time – everything imaginable – [deep, slow voice] “Well, we’re going to be sending a crew out there,”

I said, “Well, you better have it be a women’s crew.”

[deep, slow voice] “What are you talking about?” [hershe laughter].

“If you send a crew out here they’ll have very limited access to our space. If you send a women’s crew they’ll have the run of the place, they can talk to whoever, go where ever but men are going to be restricted to an area.”

[deep, slow voice] “Whatta ya mean?!? We don’t have a women’s crew.”

“Well, maybe it’s time for you get a women’s crew.” And CBS especially, [deep, slow voice] “If you don’t let us on we will open our story with you didn’t take the American flag [laughter].”

“Well, OK then.”

And if you go into the archives you’ll find their story – ‘…going down Rte 96 and all these flags and then boom no American flags and this is the Peace Encampment…’ They did, they were good for their word. That’s what their story was about, not taking the American flag.

E: Didn’t they also essentially do a blackout – well, lousy term, did they then refuse to send press and refuse to print anything about the Encampment at some point?

M: Not that I’m aware of. When we opened we were everywhere.

E: OK, but afterwards, continuing stories?

M: The thing about the media though, Estelle, is when you’re hot…

E: You’re hot…

M: …everybody is there…

E: …and then it’s old news.

M: …and after that it’s really, really hard. Because what we trying to focus on, we had all this media attention, is get the bullet points out. Get the, it’s not about a Buddhist nun walking hundreds of miles to show up here and chant.

E: Right.

M: It’s what motivated her to come to the Encampment because we’re up against the …

E: Right.

M: …and they were playing the same game, they were not as skilled as they are now but you’d open up the paper, ‘$300,000 spent on barbed wire fencing due to the Encampment,’ kind of stuff, yeah, right, like you didn’t want that fence. So they were playing too.

Ithaca Journal, July 16, 1983

Ithaca Journal, July 16, 1983They were playing it probably a little more sophisticated than we but we were more sensational so we got more coverage [laughter]. But you gotta know we had women wearing polyester who had probably never seen a media person in their life being the spokespeople kind of stuff and the media was going, “Who are these women?” [shared laughter]. But women came up to us and said, “I want to thank you, I have been trying to get in the field and be an investigative reporter and I could not and it was the Encampment that allowed that door to open …

H: Wow.

M: … by you all holding your ground and saying that we couldn’t have access to the true-behind-scenes-story without it being women, were given a shot.”

E: Wow.

H: That’s great, I never thought of that.

M: Yeah, that was really cool. And then the other really cool thing, so many things were just great, but the other great thing was the march from Seneca to the camp when they were stopped at Waterloo and arrested and everything. Not one woman, when people were taunting them, ‘Dirty Lezzies, dah dah dah, Kill you dah’ … not one woman said, “I’m not a lesbian.” But as people came back to the Encampment after court, and, so many straight women said, “We had no idea. It was so eye-opening to have that kind of hatred focused at us and all we had to do was say a few words and that would have been different and we stayed true to our commitment and we had no idea of what you all go through everyday of your lives.” And I think they’re probably the strongest allies having been created that one day in terms of …

E: Had the term, ‘political lesbian,’ I remember, do you remember Jodi Trout?

H: She was ‘85.

E: Yeah, that is later, but by then a lot of women who might not have been lesbian, who were not out lesbians definitely and who might have been straight women would say, “Well, politically, I’m a political lesbian.”

M: Oh, so not practicing sexually but...

E: Right, but…

M: … believing.

E: … aligning with lesbians and for political purposes and that became a term and I wanted to ask you that a little bit earlier, had that term existed before?

M: I don’t remember that. I think that in the early days when there was such upheaval, you know how we always need to get a definition on things I think that might have been the beginning of a need for definitions because I don’t believe a lot of women wanted to relate as being a heterosexual woman because of all of the privilege that could mean and they didn’t want it but also because those women identified so much more with out politic. ‘Political lesbian’ I like that, that’s good.

E: Yeah.

M: I wonder is that still used? I don’t hear that.

E: Well, I heard it over the years a lot but then I hadn’t been out as a lesbian at that point so, or, that’s where I came out was at the camp.

M: And were you a political lesbian before you were a full-fledged lesbian?

E: When they said that, probably, probably.

M: Quite a women were, quite a lot of women were.

E: And so, I guess that’s why I probably have held onto that term and remember it. I thought about that a couple of times and wanted to find out, had that been a term that was used, that many people remembered, or had that had, a beginning?

M: Leeann might remember that more.

E: Okay.

M: So many changes, so many changes. I’ve seen women afraid to come there because of the lesbian tag. But when it first opened that lesbian tag hadn’t taken route yet. It had been put out there a little bit but everything was in motion, people were coming anyway, the lesbianism was not, it was the woman thing. It was the women taking the power and drawing the lines of who could go where. We had some people from one of the native tribes doing the opening. I think she was from the Turtle Clan and we had the, the nod from A.I.M. (15) as being this is a good thing to support and we just had the Buddhist colony and we had Dr. Spock (16) and Bella Abzug (17) show up.

Bella Abzug at Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice. Nancy Clover, July 1983

Bella Abzug at Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice. Nancy Clover, July 1983We had everybody. We had hundreds and thousands of people come there. We collected so much money. We had money. We paid off, that farm was 100% paid off. And then, after it had all died down and all of this stuff is in place and we’d cut the fence 1000 times and they’d climbed up the water tower and wrote the famous stuff and arrests everyday. It was pretty interesting because we had ongoing civil disobedience trainings and that was War Resister’s League, it was a lot different groups coming in to do those trainings. That’s where I first met Mandy Carter. Even though Mandy and I were both from Albany I’d never met her before. And so that was the first time that Mandy and I got together. So they were doing trainings and then ‘whoosh’ down to the fence, down to the gate [hershe laughter], they’d get arrested.

Women at the truck gate – Seneca Army Depot. Nancy Clover, August 1, 1983

Women at the truck gate – Seneca Army Depot. Nancy Clover, August 1, 1983It was like this ongoing revolving door and you could only be arrested so many times before, you know, that kind of stuff, right. And so I think a lot of activists were trained through the Encampment, a lot of women who then went on to be activist within the queer movement got their training in, in, at the Encampment and that’s where, I know later on when I went to, in ’86, I went to a meeting in NYC because there was going to be a march on Washington and this guy, John O’Brien from L.A. stood up and said, “Hey, you know what? Let’s get the whole march and take a left and go over to the White House and storm it.”

And I was in shock and I stood up and said, “You can’t do that, civil disobedience is a whole process here, this is a consciousness-raising, this is something you have to sit with and really examine what you’re saying, where you’re willing to go with it and this is not a photo op. This is, this is old-time, the reason you want to be in the court is so that you can make a statement from your heart and have it recorded within our system and not only that, you have to think about your plants being watered, your cats being fed, your bond being paid, your job being lost, this is not, ‘Hey, let’s go take a left and go storm the Whitehouse.’ What’s wrong with you?!?” And so they say, “Oh, okay, Crone, then you do it.” And that’s how I ended up organizing the civil disobedience at the Supreme Court against the Hardwood decision (18). But that was a lot of training ground for women.

E: You know, Michelle, after that night when we all got arrested it was like all eyes were on the Encampment women they’d lean over and go, [modified voice] “What’s next?”

And we’d say, “We don’t know about you guys, but we’re forming a circle.”

[modified voice] “Oh, okay.” They’d form a circle. It was like they were trying to pattern themselves on whatever we did, they were going to do.

M: Yeah, well, Act-Up (19) came out of the organizing for the march, so Act-Up came out of the Encampment except that Act-Up didn’t want to do so much process [laughter].

E: Right, right. Even on the bus, they were taking whatever the women did and they would watch. We were getting out of the handcuffs because we had learned how to do that [laughter] chi thing of making your wrists really big when they put them on and then shrink…we’d come out of them. And we had clippers but that was, I felt like they were watching us and learning from us and following whatever we did. It’s like, “Pass the clippers back.” You’d make this little action and put your hands behind your back and pretty soon it was right down the bus nobody had handcuffs in the whole bus. And when we went to be processed they were watching everything we did – “Change clothes. Do anything you can that makes the process take longer, that confuses them.” [inaudible] … the pictures that they’ve taken don’t match.

M: Well, the booklet that was created for Seneca is still to this day, I think, one of the most comprehensive and just a wonderful document. I put a few of these in the archives that I gave to the New York state university there. In ’87 we used that booklet for the foundation for the booklet for all of the civil disobedience at the Supreme Court. [motioning to camera] This is blinking, is that…?

H: I was thinking it’s getting down on its tape. It’s just letting me know we have a couple of minutes left on this tape. Were you arrested, did you do CD that summer?

M: No.

H: Okay.

Nancy Clover, 1983

Nancy Clover, 1983M: Unfortunately one of the drawbacks of being one of the most responsible for things in terms of how the, it operates, is you have to keep it going, you have to keep it going. I was not able to go over the fence. I wasn’t able to cut the fence. I wasn’t, but I was able to make sure that everything was in place for going over and cutting and getting out and all that was in place.

E: Yeah.

H: And was there a discussion, I’m curious about a discussion in terms of non-violence - when people originally imagined CD was it going over the fence? Did the cutting, was that something people talked about – cutting or entering?

M: When you do the non-violence and you form your group, your group comes up with what the, what it’s, what they’re going to do, what the action’s going to do, following a theme and our theme for being there was for educational purposes, for letting them know that they don’t have the power at all times, that they cannot dictate everything that gets done in a certain way that we wanted to disrupt that whole process and make them know that they weren’t all-powerful, that they were vulnerable. And that’s when the war started. I really do, I call it a war because not only were they cutting our water lines but one night sitting in the office, hearing a thump next to my head on the wall and going out and finding a hunting arrow…

H: Oh, okay, that was that incident.

E: Uh-huh.

M: …that had this metal, jagged metal, that if it had been six inches over it would have hit our propane tank.

E: Yep, I remember that.

M: Yeah. And I’ll never know really were they aiming for the tank? Were they really going to blow us up? Or were they scaring us? I don’t know. It was dark.

E: There was something with shots to the front door…

M: Shots all the time and then we started to have to form our own policing the outer areas looking for men because they were coming over.

E: That was a little bit later on. That wasn’t in the beginning.

M: No, not in the beginning.

E: We had security, and, but it wasn’t, it became a little bit more …

M: Escalated.

E: …ugly later on.

H: And you thought that was from the military more than townspeople or a combination of both or…?

M: I think it was a combination of both. I think it started with the military…

H: You think it started with the military?

M: I know it started with the military because we were told that they were the ones that came over and started cutting our water lines.

H: This is from Shad, the person …?

M: The guy. And it, it’s kind of strange, as the lesbianism thing grew more visible, more accusations were throwing at us – we wanted to steal the kids, we wanted dah, dah all this kind of stuff...

E: The women [laughter].

M: The women.

E: All their women.

M: Yeah, we were probably blamed for everything that ever happened in that county. It was our fault [hershe laughter]. But the longer it stuck out the more that the authorities then, I think, came to respect, on some levels, what was happening there because then women would be dropped off at the encampment by the police.

Nancy Clover, 1983

Nancy Clover, 1983E: Right, right, and I think that’s really true, because then there was the thing of, when the depot wanted to, were dropping, after women were arrested they were putting them out at side gates, gates that were way far away. The women were having to walk in, on dark roads. Some of them almost got hit by cars. The police couldn’t have that.

M: Yeah.

E: The local police became, they were, there’s a lot of ways that they were really great. The authorities meetings, I eventually became involved in the authorities meetings and that went on for years and years and I do think that we had, some of us had…

M: And this is where, I know that Louise’s book (20) is not well-thought-of…

H: Um-huh.

M: …but this is also where Louise having spent a lot of time with the local people...

E: Yeah.

M: If you do want that kind of data …

H: We do want …

M: She’ll be invaluable to share that with you guys …

H: Do you know how to get a hold of her anymore?

M: I have an old number for her in out in L.A.

H: L.A.? I think that was, we tried to do research just online trying to track down women so any lead is helpful.

M: The last I heard of her she was a professor…

H: Okay.

M: …at, I think it was U.C.L.A.

H: Okay. So we’ll…

M: …and she married a anthropologist from SUNY Albany. I’m sure you could track her down through the alumni of SUNY Albany.

H: Great.

M: Yeah, that’s where she got her doctorate from.

H: She’s got to have, we want to check out those interviews.

M: Right.

E: Does she use her married name?

M: I don’t know

E: Would we need that?

M: I don’t know, but you can also get that from them.

H: We’ll find out.

E: Yeah.

H: Great.

M: So, the Encampment [laughter], so I’m sure that you know about the money stuff, right? So much money was raised and we never, ever expected that much money was going to come through or that many people were going to come through. We were very successful. We brought the attention to the rural military presence in our country. We started the educational process within the counties even though they didn’t want it, they needed to face up to the fact that white animals and high cancer rates and being dependent on the military bases were not really to their benefit. We educated, we gave a chance anyways for women, young women to become educated to the possibilities of having other options open to them in life rather than the same patterns that they normally would have just fallen into. There were a lot of conversions of heterosexual into bisexual into lesbianism that I saw but that always happens when women come together. There was a lot of development of women ritual. This is important, it’s not just that, it’s not just that women were borrowing from the native traditions, they were, but Seneca created their own rituals. And powerful rituals and…that continue to this day.

H: Tell us some.

M: Well, circles forever, those beautiful paintings on the barn - that all came from just blossoming of spirit. Fire circles, affirmations, focusing energy – yeah, we cut the fences and went in and painted but we also circled before we went in, we envisioned what it was that we wanted to accomplish, we shifted energy into making things happen and this is not something that we thought maybe would work, we knew this to work.

H: Where did you know that? Stuff you brought in? Did women bring in from other parts, other circles, other experiences?

M: Yeah, but also we created it.

H: …created that.

M: We created it and it was a blending of lots of traditions – like a lot of Buddhist stuff, a lot of, I don’t want to say Wicca (21), it wasn’t Wicca, it was just lesbian equivalent of doing that kind of magic with circles and focus and feathers, rocks, shells, drumming - it was all happening there and people would come in and “we did this at Puget Sound (22)” and other people would come in and say, “We want to do a peace encampment can we study with you all?”

“Absolutely.”

Really the outreach from this little place in upstate New York was tremendous, tremendous. I remember early on I seeing this woman walking up our driveway carrying a guitar wearing a green felt hat and came to the door and she said, “Can I stay here?”

And I said, “Yeah, you can stay here.”

And she goes, “Do you need any help?”

I said, “Absolutely, here can you vacuum this room?” And that was Myke. [hershe laughter]. And you know, Myke who is now a minister and continuing to do the peace work kind of stuff - it just keeps going. Seneca was a training ground and we did it all on our own in terms of women. We did it with women. Men wanted to know how to help and we were always saying, “Give us money, give us money. You have it, give it to us.” But pretty much it was all women’s energy that created that space.

Nancy Clover, 1983

Nancy Clover, 1983H: What was it like for you personally to be involved in something that, had you been involved in anything that successful, that went like that? Or what was it just like personally being a part of it?

M: I started out organizing in the late 60s so in terms of organizing it was, it was like working in an ocean of chaos, and because the decision-making was so broad that, in organizing and decision-making you often need to be able to make one fairly quickly [hershe laughter] in order to take the next step. So that was challenging and I have to say sometimes I just couldn’t, I couldn’t wait, I had to just do things and then I would come back and explain kind of stuff because you just, you couldn’t go and have a consensus about whether or not you should sign something in order to go to the next step. You, it was creative because you’re, myself because I had eye on the goal of getting open legally so we wouldn’t be closed down. At one point right before the opening, it was like, would they even allow the women on the land or were they just going to ship us all off. And then it was a lot of, and I do a lot of facilitation stuff, it was a lot of facilitating between major personality and belief systems clashing - it took a lot of my energy, a lot of it. But at that time that’s what I did, and I learned that from working with women. I had a professional company facilitating in the later years and I would go to the International Facilitation Association meetings and I would go into a workshop on chaos and you would have to identify where you are on the line of, of work, on being able to work in chaos one through ten [hershe laugher] and I would take the chalk and I’d go over to a, I’d create 30 [hershe laughter] and they’d go, “What are you talking about?” And I would give them an example [hershe and Estelle laughter] from the Encampment or from the [inaudible] or from the festivals. All my life I’ve been in the midst of the chaotic kind of craziness that we create when we’re moving along. It was a great training ground for me too, and it was wonderful people and I’m really glad that I, I got Louise to do her dissertation on that because I wanted to legitimize within the academic world the Encampment because I knew the importance of what was happening there and didn’t want it to just be isolated as some crazy little thing. I really wanted it to go into another realm so even though Louise’s book was not well-accepted, I’m glad she did it.

E: Yeah.

M: I’m really glad that that is out there.

E: Michelle, the amount of chaos. I’m thinking about, there was a kind of volcanic eruption that the Encampment created, okay? And even, when we talked with Carrie [see PeHP Herstory 001], because of what then began to happen in the community, she felt she had to pull away, there were things that she couldn’t…

M: Yeah.

E: …couldn’t deal with and you’re taking about the chaos chart [laughter] at 30 and I’m thinking about change and how, and for lots of people that was, the amount of chaos is very difficult, it’s like, because they can’t see the forward movement…

M: Yeah.

E: But you, you knew it to be happening and, to some extent, or could you see that it was happening?

M: Yeah, from the festivals…

E: Uh-huh.

M: …when we were doing Michigan we would get seven, at that time, seven or eight thousand people in there and it was very similar in terms of different classes, different identifications…

E: Uh-huh.

M: …having to share, live in that small village and because I created the rumor control and the political tent…

E: Right, right.

M: …having to be the frontline stuff…

E: Uh-huh.

M: …then yeah, I was, I personally was able to have some historical reference points that, this is not out of control, this is totally to be expected.

E: Right…

H: They didn’t have that.

E: …okay because I can make the connection but the festivals have a beginning and an end, okay, a period of time that they’re going to be meeting for…

M: Right.

E: …and you have, so you have all this stuff happening…

M: Right.

E: …and resolution has to happen to some extent, fairly quickly and what I know is that when you go to festival you learn, you learn at an enormously speeded up rate almost. It, it, I want to say if you’re lucky or if you’re wise you start taking it in at a really fast, because the pace is really fast and the Encampment was that way so I’m seeing that there is, there is a way that happens at a speeded-up rate when you have those situations and, I guess I’m trying to, I hadn’t realized that as much as hearing you talk just now making the connection, of why we, why I so hunger for the Rhythmfest, for the, that I don’t have that in my life now…

M: Yeah.

E: …and it’s, and it’s hard Michelle. I feel like I’m not growing in the same way or at the same rate. There were things that were happening to us – like them and don’t like them – it’s good and it’s bad and it’s hard and it’s wonderful – all those things…

M: Right.

E: …but there’s a big variety of emotion that you’re going through and having to process at a very speeded up pace and I remember the last one beginning to feel like we were actually starting to do telepathic communication. I was not having to [laughter] run around as much – that people were sending me messages of, “I’m already taking care of the ramp at the stage…

M: Um-huh.

E: …I’m doing this and this as far as accessibility went.” And then I felt like, “Oh my god, we’re doing it, we’re doing it!” It was really happening.

M: Um-huh. Well, that kind of stuff was not only validated at the Encampment but really encouraged. There wasn’t, we didn’t bring the baggage from the mainstream in that only nutty people would rely upon psychic kind of connections, we really tried to reverse that way of thinking in terms of validating it and trying to get rid of the garbage and the channels prevented that stuff from happening. It was like a whole new world that incorporated a lot of the historical – women were trying to bring in what other strong women had done in the past with the native connection and the peace activist connection and all of that and what you’re doing now is really important because it really has kind of like become more difficult to organize in this environment of the Bush administration taking away all the civil liberties to even question and I would say to you when you collect your data if you can bring in some social anthropologist to do the analytical stuff…

E: Yeah.

M: …and looking at it from a lot of different levels around social change and women’s empowerment…

E: Uh-huh.

M: …and challenging the, the, the powers-that-be because this is the kind of stuff that needs to go back into the world of academia. I really believe women need to study this in women’s studies classes, in race and gender classes, in all of that.

E: Uh-huh.

M: And that’s again something that…what’s her name? Why am I spacing out? Krasniewicz.

E: Louise.

M: Louise, Louise. That Louise can maybe help with. But I think it’s so important that we attach to other ways of looking at things so that we become incorporated into the history/herstory…

H: Um-huh.

M: …because they will try to push us out…

H: Um-huh.

M: …and there’s just so much that went on there, so much that continues because that there was there…

E: Uh-huh.

M: …I remember one time I was asked to speak at the N.O.W. (23), the national N.O.W. conference and I spoke only about the festivals and those women didn’t get it, [laughter] they just didn’t get it…

E: Uh-huh.

M: …but it was all about women being empowered and challenging the powers that have control and…

E: Uh-huh.

M: …at the Encampment that’s all we did, “No, we’re going to build this whole barn ourselves.”

(modified slow, deep voice):“How are women going to build a pole barn?”

“Oh, you watch us.”

And they, we, did. They came out in trucks, lined up along the side of the road – we were doing the pole, the electric, the gas-powered pole thing that would throw women off. They started and whoops, there goes another woman [hershe laughter]. And you could see the guys in the trucks kind of chuckling [hershe laughter] and another woman would go in there – Samoa really was the best [hershe laughter]. She would hang on and just go down, down, down. Women would show up like, [modified high voice] “I don’t know how to do that, I’ve never done that. I don’t know how to do it.”

Nancy Clover, 1983

Nancy Clover, 1983“Well, here you put your hand here and put your hand…” And three months later you see that same woman with a tool belt going out into the back to repair something or to build something on the kitchen and it was just an amazing, amazing learning experience, an opening experience, opening to people’s, to women’s potential.

H: When did you, when is your range of involvement with the camp? Does it have a beginning and an end for you as far as when you say the peace camp was this or the peace camp was that?

M: From the beginning meetings to, I don’t know, we opened in eighty…two.

H: ‘83.

M: Or eighty three and…

H: You were supposed to close at Labor Day and you had the big meeting in Albany in the fall of ’83 that it wasn’t going to close.

M: Yeah, it was kind of like, “Oops, we didn’t think past that [hershe laughter] opening thing did we!” Yeah, and that’s such a shame, such a shame. My feeling…

H: What was a shame, tell us.

M: It was a shame that we had to do what we did with the money. Which I was a part of the committee and got the proposals and who’s going to get what and I was not for, for even doing that but there were others, a group of women…

H: Tell us what ‘it’ is, explain it for the camera.

M: Okay. When we, I think we had several thousands of dollars come through the Encampment that summer and when the Labor Day came, many of us just assumed we just keep going and we would shift a little bit of course but there was a group of women who said, “Look, I was a part of the fundraising, I believed in the vision, we have to stay true to our commitment which was to go through Labor Day.”

And so, [modified voice] “Well, we don’t want to.”

“Well, we have to.”

And so the compromise was that we would take all the money that we raised, ask for proposals that went along the lines of what our whole vision was for the Encampment and then we would give the money out. I think we kept a little bit of money for tax purposes but not enough, certainly not enough. And so we did, we looked at things. I’m sure there has to be records of who received the money and there were some pretty creative proposals that came in from women and I think they had to have a connection to the Encampment. The idea, maybe, was born at the Encampment or somebody came and felt empowered from the Encampment and they want to go back to this community and open up some kind of women’s resource center – along those lines. I’m sure that that documentation must exist somewhere. Where are the records?

H: We’ve been at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe (24). That’s where the archives are.

M: Did we put all those records in there?

H: That’s where…

E: I hope so, but you know Michelle, a lot of things…

H: There’s 12 file boxes but there’s a lot that I don’t think is there that I think individual women have that we’ve found just in talking – tucked away in their storage or something.

E: Yeah.

M: But also, was the Encampment, was it abandoned?

H: [inaudible]

M: Oh thank you [inaudible] [laughter].

H: We also got…

E: It was never totally abandoned. We’ve had period of times when nobody was living there.

M: But were the records there?

H: The records were moved.

E: No, most of the records had already been moved…

H: To the archives.

E: …what was found. But also there were, things got lost over the years, things got taken, things got…

M: Yeah, it was a pretty open space [laughter].

E: Yeah, a pretty open kind of thing and at another time when we thought it was going to close, it was, “Well, if there’s something here that you need or, maybe you should take it because we don’t know if we’re going to get through…

M: Yeah.

E: … [inaudible] through the next winter.”

H: But as far as the records women did a really good job of moving most of the records to Schlesinger and even when we were there last October…

E: Uh-huh.

H: I went through everything that was on the land to see what might be useful for the Herstory Project which I’m glad we did now because we didn’t realize…

E: Yeah, I didn’t [inaudible] [laughter].

H: …the land would be gone…

E: Yeah.

H: …but

M: Do they have researchers putting the…

H: [inaudible] together?

M: Yeah.

H: Well, it’s Jacalyn Blume…

E: Yeah, I don’t think that, I was able to look at some things and go, “No, no, no this is mis…, this cannot be a meeting at this time, it to be either before or after.” There are things that you can tell they tried to put together or make order but stuff goes, just bunches of paper…

M: I can maybe help you with some of that identifying.

E: Like even the photographs…

H: That’s what they asked us…

E: I was recognizing lots and lots of people and…

M: You know Louise, when she was doing her research, I gave her a couple of bundles of papers from the early, early years of media…

E: Uh-huh.

M: …and meetings so…

H: See, I think a lot of really good stuff is, like you’re saying, either Louise has or women that, Andrea has stuff… women have things that I think is important. I was actually pretty disappointed in the collection. We spent a week…

E: Yeah.

H: …going through the archives and I thought it was pretty sparse as far as…

E: Yeah.

H: …and then the photographs are just in a big folder, no sense of who they are or when it happened…

M: Hmm.

H: So I think, we met Jacalyn…

E: Yeah.

H: …and she did the best she could I’m sure but…

E: Well, and she was excited, and she was excited to meet us. She had been on it, I think, from the time, the beginning, right? She worked on…

H: She was the one that did it, yeah. She was the…

E: So…

M: See, in the fall in, I’m going to speak to the graduate student class at SUNY Albany and try to get two students excited and interested to go into my papers and start putting them together.

H: That’s what we saw, I downloaded, that it’s still under construction or whatever, so okay, that’s still true.

M: So, alright in the beginning, so my little apartment, mostly I kept that apartment because I just, it was like a library unto itself and then when I had to leave and they had started this and wanted my papers and California wanted my papers and I said, “No, I’d rather keep them in upstate New York.” So I started, okay, this would go to the, Seneca and this would go to the Festival, and this would go to the March… after a while it was like, ah, I can’t, here! And I threw them into a big box. My personal papers I would try and separate and after a while it was like, “If they really want to know what a lesbian organizers life was – have it all!”

[modified voice] “Dear Crone, I hate you. You did this to me, fuck you!” [hershe laughter].

I just threw it all into the boxes. “If you really want to get a full picture – here. [laughter]. That’s what it was like.” [hershe laughter]. So I don’t know who’s going to ever really read it, but it’s there. The whole picture is there.

H: Why does it say that some of your stuff is at Cornell, too? Is that…

M: Yeah, because some of my stuff…

H: From ’97.

M: Yeah, some of it went to Cornell. You know what’s in Albany though, we were talking about ritual? The hula-hoop ritual, remember there were a bunch of hula-hoops that we would take fabrics and feathers and stuff? I had those hula-hoops under my stairs.

H: So they’re kept somewhere?

M: Yeah, I threw them into the Albany collection.

H: That is great.

M: The hula-hoops.

H: What about, do you have anything else that’s not papers? Do you have banners or flags or…

M: Most of that stuff we sent out to Cornell.

H: Cornell?

M: Didn’t we?

H: Or Radcliffe? Schlesinger?

M: Schlesinger.

E: Schlesinger.

E: It’s not there.

M: I swore we sent our banners.

E: I know Michelle, there’s a lot of stuff…

H: That’s what we hoped for…

E: …that just isn’t there.

M: That’s weird.

E: Yeah, yeah.

H: Yeah.

E: I haven’t seen a really, there were some beautiful banners that were a part…

M: Oh, great, great banners.

E: One favorite that I keep my eyes always looking for it…

H: And t-shirts.

E: …but I haven’t seen it.

M: You know what? I have some photos.

E: That would be…

H: You have with you still?

M: Yeah.

H: That’s what we need.

M: Yeah. I have photos of us sitting on the lawn and that little ‘13 Hugs a Day’ thing with the hands, stuff like that. Would that be helpful?

H: Yeah.

E: Oh sure.

H: Because one of the things that we’re running into at Schlesinger is that it costs .45 to copy a document and then scanning, they haven’t told us how much but they won’t let us bring in any scanner to do our own scanning of the photographs.

M: Don’t we have any, who negotiated that [laughter]?

H: That’s what I’m saying, we, I’ve read the, we want to try to get some help with that.

M: Yeah.

H: Because we want to…

E: We need access.

M: Oh, oh, oh…

H: One of the things Alice has put together…

M: …I just got an email from JEB and JEB is another person you need to talk to.

H: We contacted her, yeah.

E: What was JEB’s slide show called?

H: Slide show called?

M: The slide show of the…?

H: She did a slide show of the peace camp.

Jane Rubin from New York at the main gate of the Depot. Nancy Clover, Labor Day, 1983

Jane Rubin from New York at the main gate of the Depot. Nancy Clover, Labor Day, 1983E: I know she did so many slide shows, but the peace camp one.

M: I don’t…

E: The first one.

M: I don’t remember but I’m sure she’ll… but I just got an email from her and there’s now a new fund for women and media. It’s the Tee Corrine. Now this is media.

H: It is media.

M: So maybe you could get money from that to do your research and copying and things.

E: Uh-huh.

M: Give me your, your information. Actually I have your email.

H: Well, this is the.

M: I can just forward it to you because I have your email.

H: Yeah, you do. I just wanted to give you – that’s just one of the things we’ve been working with. [handing PeHP postcard to Michelle].

M: Cool. And there’s other…

H: It has the blogspot on the back. The main part of this is to collect the stories and what women want to do with the information, people are talking theater project, we want, we still have the book project that we’re working on…

E: And the songbook too, Michelle, we’ve got to do the songbook.

H: …any of a number of things.

M: Oh yeah, the songs were great.

E: We’ve got to.

M: Remember the woman she came, her parents were hippies and she went the other direction and she wanted to be more conservative and she came to the Peace Encampment and then she became ‘Fire’?

E: Yeah!

H: Jessica?!? Jessica!

E: Yeah, Jessica!

M: Jessica! That’s it!

H: I’d love to track down Jessica!

E: [inaudible]

M: And she would, suddenly she was getting more and more wild…

H: [inaudible] …her hair shaved off.

M: …and then she would stand on the rock in the back and sing opera to the military guys [laughter] and I kept thinking, “Ah, her parents would be proud.” [shared laughter]. Yeah, so I’ll go through my photos and…

H: We would love to come, where are they at here or …?

M: I have some here, I have storage in Albany.

H: I’d really love to come and scan…

M: You know that I’ve wanted for so long to create a thing called ‘Old Dykes with History’ and take it on the road. I wanted to do it with Mandy and JEB.

H: All dykes?

M: Old. ‘Old Dykes…

H: Oh.

M: …with History’ and go onto the campuses because the histories aren’t being told…

H: Exactly.